This article mentions rape and sexual assault.

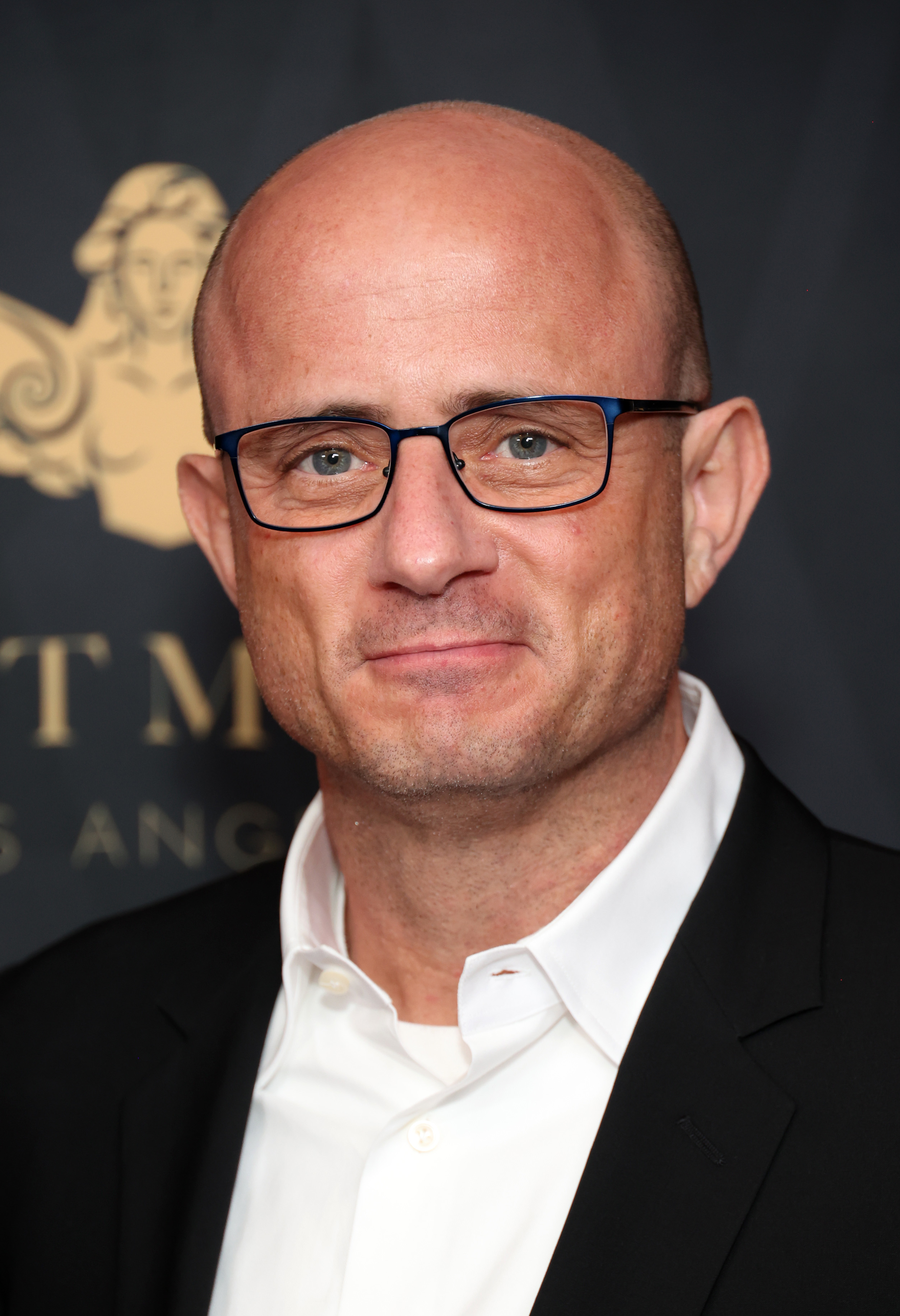

Earlier this month, The Boys showrunner Eric Kripke sparked widespread outrage when he described a disturbing sexual assault scene in the Prime Video series as “hilarious” and “comedic.”

For context, a recent episode of the hit show sees Jack Quaid’s character, Hughie, get sexually assaulted by his childhood hero, Tek Knight, and a female character, Ashley.

Due to a case of mistaken identity, Hughie is subjected to sexual torture in the form of a series of BDSM-inspired challenges, and is completely unaware of the pre-established safe word to make it stop.

Even once Tek discovers that Hughie isn’t who he thinks he is, he continues to assault him — putting a clamp in his mouth before attempting to cut a hole into Hughie’s stomach to have sex with.

Hughie’s friends ultimately end up rescuing him, and the character is seen breaking down in tears soon after. However, as he starts to cry, it is suggested that he is actually emotional over his father’s recent death, not what he has just endured.

In an interview with Variety after the episode aired, Kripke was asked: “Why bring Hughie into this situation now — kicking him when he’s down by having him sexually assaulted by his childhood hero after his dad just died?” and the showrunner’s response was shocking, to say the least.

“Well, that’s a dark way to look at it!” he said. “We view it as hilarious.”

“In the comics, there’s a great storyline where Hughie goes undercover disguised as a superhero,” Kripke added. “That was a story that Jack had always asked us to do. So part of it is, always be careful what you ask the writers for. Then we finally had this Webweaver character, and the idea of Spider-Man going down to be kink-tickled in the Batcave is just too good to pass up. I’m sorry, I just couldn’t leave that on the table.”

Elsewhere in the interview, Kripke said: “I love that it’s just such a perfect setup that he doesn’t know his own safe word. It’s just like a beautiful comedy setup that he’s trying to find it the whole time.”

And in a behind-the-scenes feature, Inside the Boys, Kripke is seen praising Colby Minifie, who plays Ashley, for her “world-class comedic performance” in the scene.

Needless to say, Kripke’s approach to such a sensitive subject matter in his show horrified viewers, but the troubling reality is that this is far from the first time that male sexual assault has been trivialized onscreen — arguably impacting how it is viewed by society as a whole.

In fact, way back in 1997, men’s health activist and writer Michael Scarce argued in his book, Male on Male Rape: The Hidden Toll of Stigma and Shame, that the mere idea of male rape is so taboo that when it is represented in cinema, it turns into somewhat of a spectacle that is utilized to give the audience a cheap shock at no great expense to the wider narrative.

Alternatively, it is presented as an expected consequence of a male character’s bad behavior, which is primarily seen in the common onscreen trope of prison rape.

This representation, or lack thereof, only contributes to the stigma surrounding real-life survivors, who typically only see their trauma in the mainstream when it is played for laughs, shock, or retribution.

Here, we will take a look back at the way that male sexual assault has been represented in cinema over the years, and how this seemingly paved the way for Kripke’s controversial mindset in 2024.

Going all the way back to the beginning, the first mainstream movie to include a male rape scene is the 1972 film Deliverance, directed by John Boorman.

If you’re unfamiliar, Deliverance follows four suburban men who go river-rafting in a small town, and Ned Beatty’s character, Bobby, ends up being forced to strip at gunpoint by two impoverished men.

Bobby is then ordered to squeal like a pig while he is raped as his friend, Ed, looks on — a scene that has become somewhat of a cultural point of reference over the years, and is disturbingly considered to be a source of comedy.

In fact, in Scarce’s book, he details a competition that ran on WLVQ Radio in Columbus, Ohio, after the film’s release, where listeners were apparently told to call in when they heard an audio sample of Bobby squealing like a pig to be in with the chance of winning a hog roast and barbecue.

And Bobby’s squeals during his rape have become so embedded into popular culture that comedy merchandise that references the scene is still available to buy to this day.

As for the movie, the rape is never explicitly mentioned after it is shown, with the film’s conclusion seemingly placing all of the men’s journeys through the rapids as a “rite of passage,” with Bobby ultimately appearing to be less traumatized than his friends who earned physical injuries from the trip.

As a result, Deliverance seemingly set the foundation for one major trope when it comes to seeing male sexual assault in mainstream media: It will never be the core focus of a story.

Instead, it appears to be executed almost exclusively as a shock tactic in an apparent bid to “spice things up” rather than add anything of substance to the narrative.

This can also be seen in Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 movie Pulp Fiction, which includes an arguably out-of-place scene where Ving Rhames’s character, mob boss Marsellus, is raped in a shop after chasing his enemy Butch, played by Bruce Willis.

Both men end up being bound to a chair with gags in their mouths while two men — who are an undeniable homage to the attackers in Deliverance — try to decide who to rape first, but not before bringing out a “gimp,” a leather-clad sex slave, that they keep in a hole in the floor.

Not only does this scene come completely out of left field, it is also saturated with black humor as Tarantino focuses on the shock and confusion on Marsellus and Butch’s faces as they observe the gimp, which is another concerning punchline that has since become embedded in popular culture.

The dark humor continues once the men have chosen Marsellus to rape first, with the audience staying with Butch as he frees himself before spending an exaggerated amount of time deciding which weapon to use in order to save his once-nemesis.

As the audience hears the implications of Marsellus being assaulted, the focus is on Butch as he very slowly picks up a weapon before changing his mind multiple times.

The deliberately slow pace of this scene clearly prioritizes getting the best or coolest weapon over rescuing a man from being raped, and Butch's lack of urgency disregards the gravity of the situation and places the male rape as more trivial than what weapon is used to stop it.

Once Butch finally does rescue Marsellus, Marsellus is incredibly calm despite what he has just endured. In fact, without showing any signs of trauma over what just happened to him, Marsellus’s immediate — and seemingly only — concern is protecting his reputation.

Reinforcing the common misconception that rape is a threat to a man’s masculinity, the mob boss only agrees to let Butch go and put their differences aside if Butch promises not to tell anybody else what had happened.

In Dominique Russell’s 2010 book Rape in Art Cinema, she argues that when male rape is represented onscreen, “the emphasis is not on the act itself but on its economies of shame and witnessing: male-on-male rape becomes a shameful collective secret, one that tends to strengthen masculine bonds,” which is undoubtedly the case here, with Butch witnessing Marsellus’s attack the only thing that stops them from wanting to kill one another.

Both Pulp Fiction and Deliverance also feed into the idea that for a man to be sexually assaulted, they need to put themselves in a compromising situation or environment.

Rather than represent these attacks as something that could happen to any man in his everyday life, Bobby was only raped after leaving the comfort and familiarity of the suburbs for a primitive and uncivilized environment that distances the viewers watching from reality.

As for Marsellus, if he hadn’t been trying to kill Butch, he never would have entered the shop — representing his assault as nothing more than a consequence of his own deviant behavior.

Even in The Boys, Hughie was only assaulted because he was disguised as another character who, it turns out, had consented to the disturbing sexual encounter with Tek.

And this idea that sexual assault is only something that can happen to a man if he enters “dangerous territory” is never more utilized than in prison movies, which reinforces the misconception that this is not something that will happen to a man who stays within the “normal” parameters of society.

In her book Against Our Will, journalist Susan Brownmiller makes the case that rape is normalized in all-male environments such as prisons because the weaker male is “forced to play the role that in the outside world is assigned to women.”

As a result, sexual assault is arguably a widely expected or acceptable consequence of being sent to prison — a concept that is further enforced by the way that prison rape is often referenced in comedy with jokes such as “Don’t drop the soap.”

This particular punchline stems from the idea that in the communal showers of male prisons, if a prisoner drops his soap and thus has to bend down to pick it up, then he is more at risk of being raped. This trope has been used in even the most light-hearted of comedies over the years, including Family Guy and The Simpsons.

The 2007 comedy I Now Pronounce You Chuck & Larry, directed by Dennis Dugan, also highlights just how normalized this “gag” is by including a dramatic “dropping of the soap” scene in the communal showers at a fire station.

In the movie, Chuck and Larry [played by Adam Sandler and Kevin James] are two straight firefighters who pretend to be a gay couple in order to receive domestic partner benefits. When they are outed at work, the other men become wary of them — and it all comes to a head when one of the men drops their soap while they are all showering together.

In a bizarre comedy choice, there are slow-motion shots of everybody’s horror-struck faces as the soap falls to the ground, with a sense of over-the-top and exaggerated drama that the person who dropped it is now vulnerable to being assaulted.

Not only does this scene make light of the very serious issue of male rape, it also makes some disturbing and dangerous implications about gay men being predators.

And as a result of the jokes that surround the issue of prison rape, cinematic audiences are arguably desensitized to the representation of sexual assault in this context.

In fact, this representation is so normalized that when a character is sent to prison in a movie, there is almost an expectation that they will be attacked, trivializing it further.

Dominique Russell argues that the “threat of male rape becomes the primary reason to avoid prison, and, once a male character is there, its avoidance can work to shape the entire narrative,” which is particularly true in the 1994 movie The Shawshank Redemption, where Tim Robbins’s character, Andy, spends much of the film trying to avoid a prison gang known as the “Sisters,” who rape other inmates.

He ends up enduring two years of being raped by the gang, but these attacks are depicted as something trivial or minor — almost like it is a rite of passage for any prisoner.

The triviality of Andy’s rape is highlighted by the way that the film’s narrator, Red, played by Morgan Freeman, describes the frequent attacks as part of Andy’s prison “routine.”

Meanwhile, Tony Kaye’s 1998 movie American History X goes so far as to suggest that the rape main character Derek, played by Edward Norton, endured in prison was ultimately character-changing and for the greater good.

For context, Derek is first introduced to the audience as the leader of a violent and racist neo-Nazi gang, and the incredibly disturbing and racially motivated murder of a Black man that leads to Derek’s imprisonment is shown in full — ensuring that the audience has basically no empathy for the character.

It is then significant to note that the first time that anybody, including the audience, is told that Derek was raped in the prison showers during his time inside is when Derek’s younger brother, Danny, asks him why he no longer wants to be a part of the racist gangs that he used to lead now that he has served his time.

The fact that we learn about Danny’s sexual assault after this question heavily implies that it was the rape that led to this dramatic change in Derek’s character.

In addition, flashback scenes show that after he was raped, Derek forged a close friendship with Lamont, a Black inmate — further suggesting that he is now a changed man with a new moral outlook on life.

As the audience can see how much of a better person Derek is following, and implicitly as a result of, being attacked, it is arguably represented as being for the greater good instead of something that is both incredibly serious and incredibly traumatic.

While all of these examples have focused on male-on-male rape, women sexually assaulting men is also widely misrepresented in mainstream media, and is historically used as a source of comedy.

In David Dobkin’s 2005 movie Wedding Crashers, starring Owen Wilson and Vince Vaughn, Vaughn’s character Jeremy is pursued by Gloria, played by Isla Fisher, who ties Jeremy to a bed while he is sleeping, and wakes him up by straddling him naked.

Jeremy repeatedly says that he does not want to have sex with her, but it is implied that the two have sex anyway.

And in Nicholas Stoller’s 2010 movie Get Him to the Greek, Jonah Hill’s character, Aaron, falls unconscious at a party and is being sexually violated by a character called Destiny when he awakens.

Aaron repeatedly says “no” to Destiny, but the scene ends with her implicitly penetrating Aaron with a sex toy. In the subsequent scene, Aaron comes out of the room and tells his friends: “I think I’ve just been raped,” which they barely react to. This is the last that the audience hears about the incident.

In fact, neither of these scenes serve any actual function to plot or character development in their respective movies, suggesting that the sole reason the directors even broached the idea of a woman raping a man was just to get a quick laugh out of it.

This comedic approach reinforces harmful misconceptions that a man can’t be sexually assaulted by a woman, which is incredibly damaging for survivors.

The 2011 David Fincher movie The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo is one of the few films to reject this stereotype as it shows that the violent penetrative rape of a man by a woman is possible.

However, it appears to revert back to one of the same tropes seen in male-on-male sexual assault representation, with the man involved previously being shown sexually assaulting the woman who attacks him, Lisbeth, played by Rooney Mara.

Not dissimilar to American History X, this means that the victim has been dehumanized to viewers, and as heinous as Lisbeth’s actions are, they are presented to be justified as he is simply being punished for his own barbarity.

And unfortunately, little appears to have changed when it comes to the representation of male sexual assault onscreen in more recent years, with it largely remaining a taboo that follows the same tired stereotypes in mainstream media.

In 2018, the Netflix series 13 Reasons Why aired a highly controversial two-minute-long scene that showed a male character being bullied and then sodomized with a broken mop handle in the toilets at his high school.

The show’s creator, Brian Yorkey, vehemently defended this scene at the time, but viewers argued that the incredibly graphic storyline was ultimately gratuitous, and only included for the shock factor.

Meanwhile, the hit biker series Sons of Anarchy was sure to include multiple rape scenes and references involving characters who had been sent to prison, reiterating the idea that this is a normal and expected consequence for a man who has been caught committing a crime.

Interestingly, just this year, the Netflix series Baby Reindeer was praised for its groundbreaking representation of the main character, Donny, being drugged and raped by a TV executive.

While the scene was arguably still played for shock factor, the series did explore the long-term impact that the assault had on Donny, including the feelings of self-loathing and confusion that he struggled with for years afterward.

But as revolutionary as it is for male sexual assault to actually shape a narrative, it’s worth noting that Baby Reindeer is based on the creator and star, Richard Gadd’s, devastating real-life experience, which obviously impacts how the story is told.

It appears that when male sexual assault representation stems from a true story, there is the capacity for it to be explored in a realistic and sensitive way.

However, directors are seemingly only willing to broach the subject when it can be used for a cheap shock or quick laugh in fictional movies or TV shows.

To conclude, male sexual assault is believed to be one of the most underreported crimes in the world due to the shame and social stigma that surrounds it, which is undeniably fueled by the way that it is constantly depicted as something to be either trivialized, ridiculed, or justified in mainstream media.

Suffice to say, movies and TV shows continuing to use their influence to dismiss male sexual assault as “hilarious” is both irresponsible and dangerous, as well as a wasted opportunity to help survivors feel seen and offer them all-important support.

According to the nonprofit anti-sexual assault organization RAINN, one out of every 10 rape victims in the United States is male, and one in 33 men have experienced attempted rape or rape in their lifetime.

So, it’s worth remembering that for every commodified pig squeal and “don’t drop the soap” gag that we watch on TV, there are real survivors suffering — and the very least that they deserve is to have their trauma taken seriously.

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault, you can call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673), which routes the caller to their nearest sexual assault service provider. You can also search for your local center here.