Sarah Reeves sat on her couch in Eugene, Oregon, staring at her laptop screen in furious disbelief. She was reading the website of a government agency, where her mother appeared to have posted a comment weighing in on a bitter policy battle for control of the internet. Something was very wrong.

For a start, Annie Reeves, who loved to lead children’s sing-alongs at the Alaska Zoo, had never followed wonky policy debates. She barely knew her way around the web, let alone held strident views on how it should be regulated — and, according to her daughter, she definitely didn’t post angry comments on government websites.

But Sarah Reeves had a more conclusive reason to feel sure her mother’s name had been taken in vain: Annie Reeves was dead. She died more than a year before the comment was posted.

In the spring of 2017, a virtual war was raging over the future of the internet, much of it through comments on the website of the Federal Communications Commission — the government agency responsible for regulating the broadband industry. Reeves wasn’t the only ghost to get sucked in from beyond the grave to do battle on behalf of giant telecommunications companies such as AT&T and Comcast.

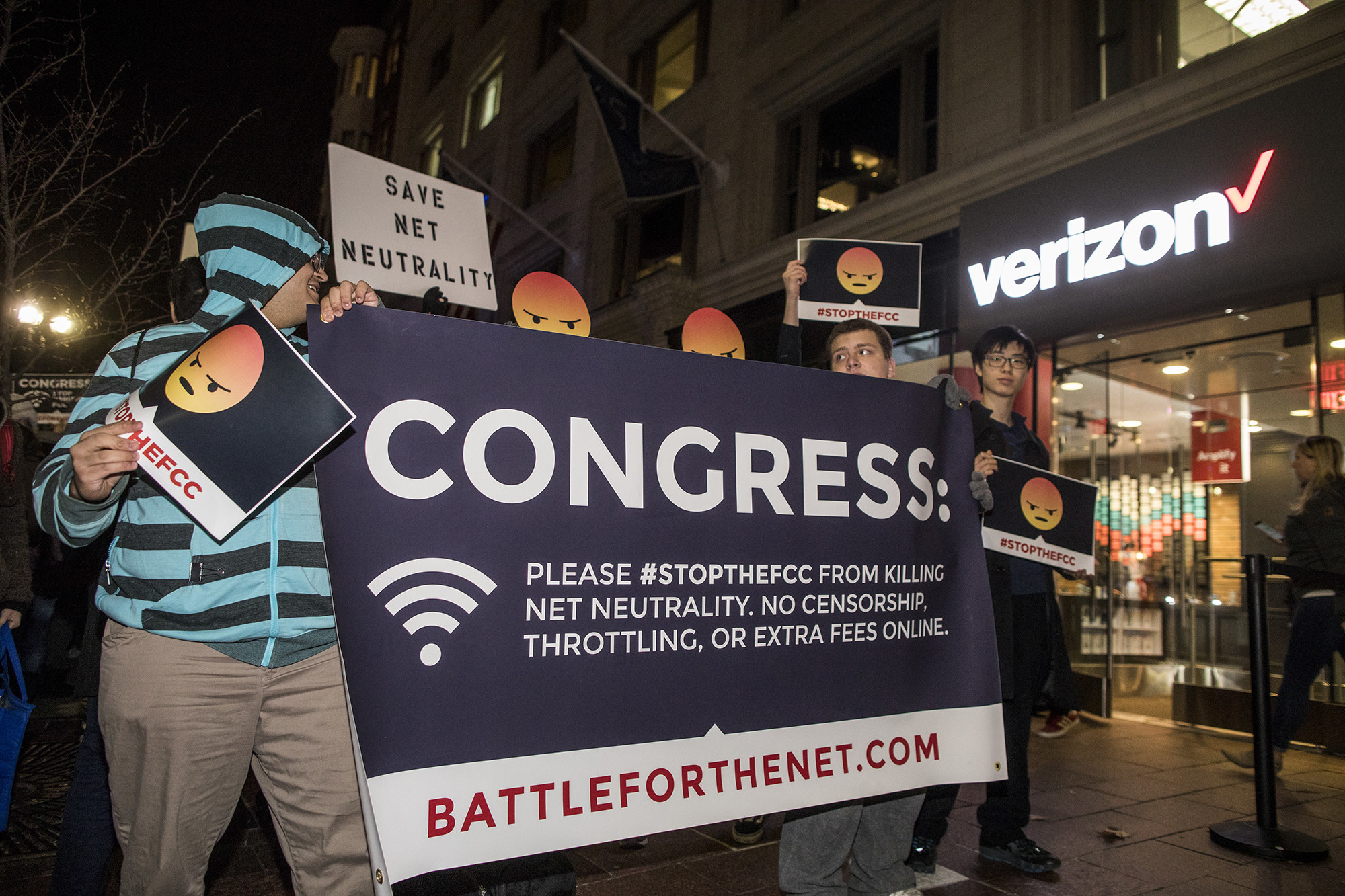

At issue was a rule from the Obama era known as “net neutrality.” It was designed to protect the open web by requiring internet providers to treat traffic from all sites equally — and under Trump, the FCC was planning to scrap it. Conservatives had long branded the regulation as an assault on free enterprise, but advocates warned that its repeal would allow the broadband giants to manipulate traffic in favor of the highest-paying platforms, crowding out competition and stifling free speech. The stakes were high, and the public comment period attracted a staggering 22 million submissions.

The problem was, many of the comments were fake.

The New York attorney general opened an investigation and has since issued subpoenas to more than a dozen entities — estimating that “as many as 9.6 million comments may have used stolen identities.” But the FCC went ahead and scrapped the net neutrality rule in a massive victory for the broadband industry and a huge blow, consumer advocates said, for users. Some suspicious comments have been tracked back to particular political operatives. But the question of how millions of identities were marshaled without consent has largely remained a mystery. Until now.

A BuzzFeed News investigation — based on an analysis of millions of comments, along with court records, business filings, and interviews with dozens of people — offers a window into how a crucial democratic process was skewed by one of the most prolific uses of political impersonation in US history. In a key part of the puzzle, two little-known firms, Media Bridge and LCX Digital, working on behalf of industry group Broadband for America, misappropriated names and personal information as part of a bid to submit more than 1.5 million statements favorable to their cause.

The FCC proceeding is not the only public debate to have been compromised. BuzzFeed News also found that LCX, an obscure advertising agency based in Southern California, has worked on at least two other campaigns that raised similar impersonation allegations — issues that were so alarming that state legislators in South Carolina and Texas referred the matters to law enforcement. Media Bridge, a political consultancy based in Virginia, also participated in the South Carolina campaign.

The rise of political impersonation threatens a core aspect of US democracy: the process by which federal agencies canvass public opinion before enacting new regulations. The process is not the same as voting, and the results aren’t binding — but they provide a forum for public debate, and officials are obliged to consider all viewpoints submitted, making them a crucible for lobbying by powerful interests.

The internet has made it possible for these consultations to be conducted virtually, vastly extending their reach in an apparent leap forward for digital-era democracy. But there’s little stopping anyone from submitting statements under fake — or misappropriated — identities.

The anti–net neutrality comments harvested on behalf of Broadband for America, the industry group that represented telecommunications giants including AT&T, Cox, and Comcast, were uploaded to the FCC website by Media Bridge founder Shane Cory, a former executive director of both the Libertarian Party and the conservative sting group Project Veritas. Cory has claimed credit for “20 or 30” major public advocacy campaigns in recent years, including, he says, record-setting submissions to the IRS, Environmental Protection Agency, Bureau of Land Management, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, and “probably a handful of others.” On Media Bridge’s website, the company has described itself as having expertise in “overwhelming government agencies” with avalanches of public submissions, and has publicly dubbed its approach to marshaling comments the “Big Hammer.”

In the FCC campaign, Cory was working for Ralph Reed — a high-powered political strategist and titan of the Christian right who himself was working for Broadband for America. Cory, in turn, enlisted LCX Digital to find the commenters.

LCX, which in the past has also worked with Mary Cheney, the daughter of former vice president Dick Cheney and a powerful political consultant in her own right, was cofounded by John Hilinski, a digital ad man with a record of deception. He has claimed publicly that he cofounded the search engine AltaVista, which he didn’t, and that he has a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Southern California, which he doesn’t. He has also claimed that he toured in the band Jane’s Addiction — another apparent fabrication.

In a sworn deposition, a cofounder of LCX described the business as a “completely fraudulent” enterprise that had routinely faked data in its corporate work.

Hilinski did not respond to BuzzFeed News’ requests for comment; nor did Broadband for America.

A letter from Reed’s lawyer to BuzzFeed News said that any suggestion that he or his company, Century Strategies, “knowingly and willingly used the names and identities of individuals without their permission in comments” would be “false and defamatory.” Moreover, the letter said, Century Strategies had “directed its partners and vendors to follow above-industry standards, including requiring individuals to provide name, address, email, and phone number to verify who they are.”

The letter added that “Century Strategies also was assured by these vendors that they utilized extensive data validation to verify all names and addresses using public databases.”

Media Bridge also vigorously denied engaging in comment fraud. A letter from Cory's lawyer, Bob Barr, a former Georgia representative, accused BuzzFeed News of preparing a “hit-piece” and noted that “Media Bridge professionally submitted comments to the FCC without hiding its identity, and provided contact information in the event there were any issues with their submissions — unlike the individuals who submitted many millions of comments from adult websites, foreign accounts and clearly fabricated data sets.”

LCX and Media Bridge are far from the only operators whose comment campaigns have been called into question. Fraudulent comments on both sides poured into the FCC during the net neutrality debate, and are an increasing problem for policymakers at the state and national level.

Still, the way the LCX and Media Bridge were able to overwhelm the FCC with questionable comments lays bare a new weapon political consultants can wield to promote the interests of the powerful, with potentially shattering ramifications for democracy.

“Spend a million dollars with Media Bridge,” Cory's company told prospective clients in a post on its website, “and most likely, you’ll have a million people + advocating for your position.”

THE FIRST BATTLE

The battle lines of the 2017 comment war over net neutrality were drawn in 2014.

Tom Wheeler, President Obama’s appointee to head the FCC, announced the agency would consider two competing approaches to prevent internet providers from blocking or slowing down access to certain websites.

Federal agencies publish thousands of proposals for new rules every year, and whenever they do, they are almost always required to put the plans up for comment. Anyone can weigh in, and the agency must take all viewpoints into consideration.

Officials insist that it’s the substance of the comments — not the quantity — that counts, but agencies often do publish tallies, potentially giving a boost to whichever side of the debate assembles a better cheering squad.

When the FCC opened the 2014 net neutrality proposal up for public comments, both the telecommunication industry, on the anti-regulation side, and progressive consumer groups, on the pro-regulation side, ran campaigns to flood the agency with responses from everyday Americans.

John Oliver dedicated a 13-minute segment to the topic, introducing the once-obscure debate to a mass audience. Despite its boring name, “net neutrality is actually hugely important,” he told viewers, later drawing comparisons between internet providers and the Mafia, and suggesting that “Protecting Net Neutrality” be rephrased to “Preventing Cable Company F**kery.”

At the end of the segment, Oliver exhorted his audience to send comments to the FCC supporting the cause. “We need you to get out there and, for once in your lives, focus your indiscriminate rage in a useful direction!” he said. “Seize your moments, my lovely trolls!”

The broadband industry, meanwhile, plowed millions of dollars into lobbying campaigns to drum up opposition to the ruling.

Cory says he helped the conservative nonprofit American Commitment muster nearly 800,000 submissions opposing net neutrality — a vast proportion of what was, at the time, the biggest-ever public response to a federal consultation, with nearly 4 million public comments.

American Commitment claimed a “landslide” victory. Still, the FCC’s five commissioners voted 3–2 to pass a strong version of the net neutrality rule, with Democrats in favor and Republicans opposed. By 2015, the obligation to treat all traffic equally had been imposed on all broadband operators in the US.

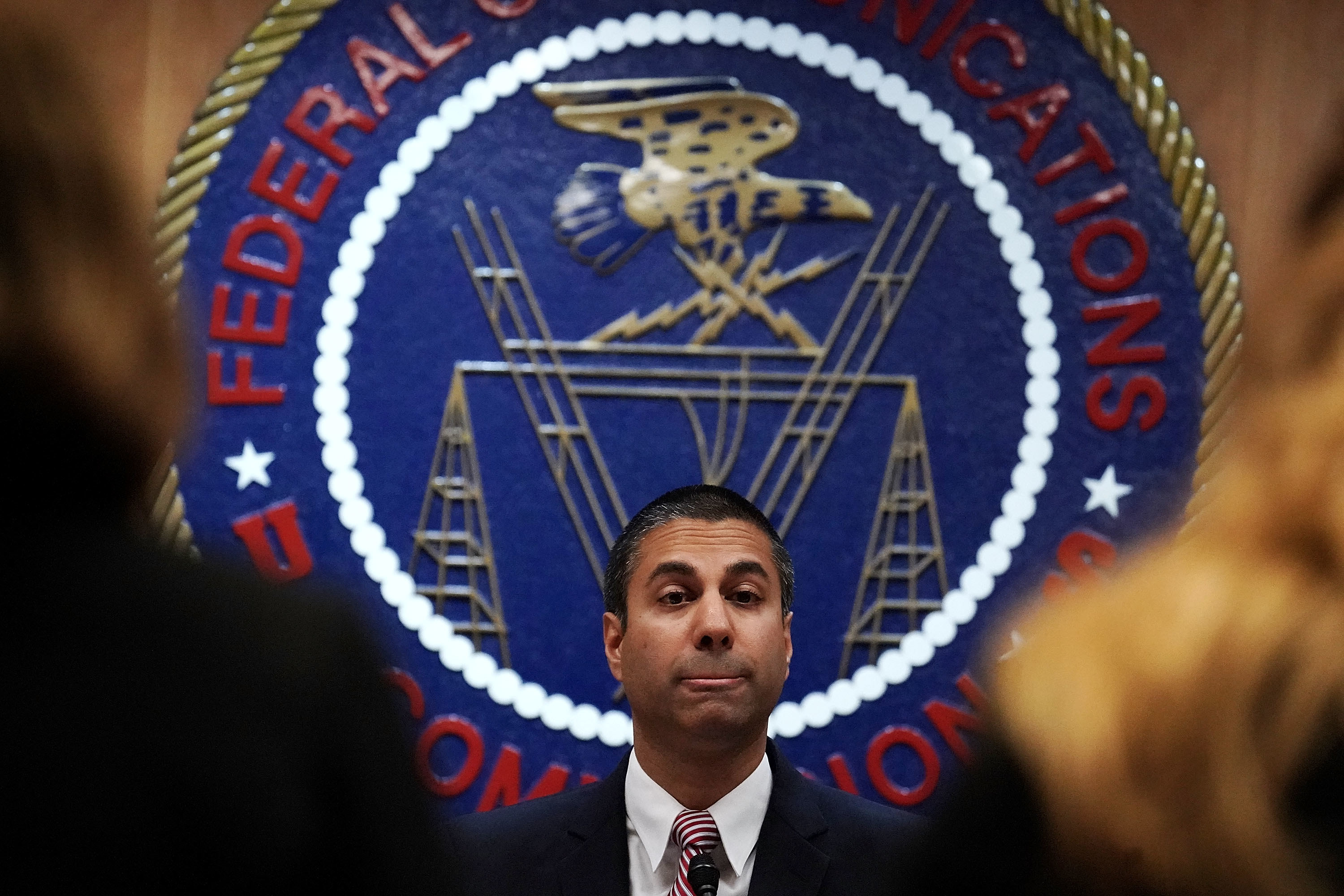

Then Donald Trump was elected. And his new appointee to run the agency, Ajit Pai, soon took aim at Obama’s “open internet” rules.

When Pai opened the repeal plan for public comment in the spring of 2017, both sides of the debate squared up for a rematch of the earlier fight.

Oliver again called on his viewers, causing such a flood of comments that the FCC’s website crashed.

The telecom side got to work too. Suddenly, despite polling showing substantial support for net neutrality, Americans appeared to be flocking online to defend the rights of the telecom giants.

Almost immediately, observers started sounding alarms. The tech publication ZDNet found that “anti-net neutrality spammers are flooding FCC's pages with fake comments” and that several people whose names appeared as commenters said they had not posted a word. Reporters at Gizmodo and the Verge found similar examples.

Pro–net neutrality comments were called into question, too. Nearly 8 million identical one-sentence comments supporting the existing regulations were tied to email addresses from FakeMailGenerator.com. Many of those used plausible names but with nonsensical street-and-city combinations that do not exist. Another million comments, also supporting net neutrality, claimed to come from people with @pornhub.com email addresses.

By the time the comment period closed at the end of August, the number of comments had obliterated all previous records, with more than five times as many as the last time the issue had come up for debate.

In November 2017, New York state’s attorney general revealed that his office had been investigating fake comments for the past six months, but that the FCC had provided “no substantive response to our investigative requests.”

"My LATE husband's name was fraudulently used after a valiant battle with cancer," one person had complained to the attorney general’s office. “This is sickening," said another, whose mother’s name had been used to post a comment several years after her death.

The day after the New York attorney general’s revelation, data scientist Jeff Kao published a remarkable finding. Using a technique known as “clustering,” Kao had found that 1.3 million comments were just iterations of the same template, generated by a computer but with certain words altered to make them seem like individual expressions of opinion. “President Obama's order to take over Internet access is a exploitation of the open Internet” was a common, ungrammatical phrase. Kao, who now works at ProPublica, also estimated that 99.7% of the “organic” comments — those that didn’t appear to be duplicates or prewritten — favored maintaining the Obama policy of net neutrality.

But a few weeks later, on Dec. 14, Trump’s FCC voted to eliminate the rule — in a 3–2 decision that fell squarely along party lines. The broadband industry had won.

By now it was clear that the public comment process had been severely compromised. But one thing nobody yet knew: how it happened.

DIGGING IN

BuzzFeed News began digging into the FCC comments nearly two years ago, submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the agency that sought “server logs” corresponding to some of the comments Kao had identified. The FCC denied that request and later denied BuzzFeed News’ appeal.

But a vital set of clues soon emerged. In anticipation of the intense interest in the 2017 net neutrality debate, the FCC had allowed people to upload comments in bulk using a Box.com account, which made it possible, in many cases, to trace who had submitted them.

BuzzFeed News requested and received details of the comments that had been bulk-uploaded through the FCC’s new system, which were first pried loose by freelance journalist Jason Prechtel.

BuzzFeed News ran large samples of the email addresses in those files through Have I Been Pwned, a website that identifies whether an address has been exposed in any of hundreds of major data breaches.

The results were stark: In one particular group of 1.9 million comments, according to BuzzFeed News’ analysis, 94% of the email addresses belonged to people who had fallen victim to a hack known as the Modern Business Solutions data breach, in which millions of people's personal information, including full names, birthdates, home addresses, and email addresses, had been stolen. In 2016, a hacker had tweeted links to the breached data, which security researchers eventually traced back to an Austin-based data management company whose servers had been unguarded.

All these comments were uploaded by Cory, using his Media Bridge email address. (Some of the comments were full duplicates; after removing them, there were just over 1.5 million comment-and-email combinations.)

In its letter to BuzzFeed News, Media Bridge contested the idea that email addresses showing up in breached databases were a sign of improprieties. In fact, it said, a “high match rate” is a sign of validity, since most Americans appear in breached databases.

Of course, there are many sets of breached data floating around the internet. But no other major uploaders of bulk comments to the 2017 FCC docket had such a close overlap with Modern Business Solutions — or any other cache of breached data documented by Have I Been Pwned, for that matter. None of the other major uploaders’ comments overlapped with Modern Business Solutions by more than 50%. (For more details on BuzzFeed News’ analysis, click here.)

Upon closer inspection, BuzzFeed News determined that the group of comments Media Bridge had submitted included precisely the same algorithmically generated statements that Kao had discovered. (The rest of Media Bridge’s comments simply used one of a handful of prewritten statements.)

Even the names, in some cases, were red flags. Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley and Arizona Rep. Ruben Gallego — both Democrats — appeared to advocate against net neutrality, contrary to their party’s position. Merkley has previously said he didn’t write the comment attributed to him, and last year he called on the FCC to investigate its fake-comment problem.

In a statement, Gallego said he had not known about the comment in his name until BuzzFeed News told him about it. “This constitutes identity theft and should and can be punishable by law,” he said. He called on the FCC and the Department of Justice to “take steps to determine who is behind this and to prevent this from happening again.”

Rep. Greg Walden, an Oregon Republican, meanwhile, seemed to have weighed in from his Oregon home address rather than his House office, using an AOL email address rather than his official House account, despite the fact that as one of the most powerful legislators in the country he would have many more potent ways to make his views known. Walden never submitted that comment, a spokesperson told BuzzFeed News.

Fictional characters had also chimed in: Boba Fett and Luke Skywalker made their cases against net neutrality, although they claimed to live in Colleyville, Texas, and Marietta, Georgia.

In its response to BuzzFeed News, Media Bridge said its campaigns, "like all others, rely on data that is inputted by individuals; which invariably includes comments from 'Star Wars' characters, politicians, other characters and even deceased individuals."

However, not only did the email addresses of Merkley, Gallego, Walden, Fett, and Skywalker all appear in the Modern Business Solutions breach, but the names and street addresses were exactly as they appeared in that breach, according to screenshots provided to BuzzFeed News by security researcher Bob Diachenko. A separate spot check by BuzzFeed News of 100 randomly selected Media Bridge comments revealed a similar pattern — even down to a street address that used underscores instead of spaces. A real person, such as Gallego, could certainly have their real information in a breached database and continue to use that real information as they moved around the internet, including submitting comments to federal agencies. But it seems impossible that so many people would have done so, including people such as “Luke Skywalker” supposedly living in a small town in Georgia.

In defending its submissions, Media Bridge pointed out that the full universe of net neutrality comments in 2017 included five from “Hillary Clinton” and 15 from “Barack Obama.” That’s true — but none of those comments used contact information that matches data in the Modern Business Solutions breach — except for the one “Barack Obama” comment submitted by Media Bridge.

CURIOUS MATH

After finding the eyebrow-raising patterns in the 2017 net neutrality comments, BuzzFeed News searched for other batches of suspicious-looking FCC comments.

Again, Media Bridge popped up.

When the FCC was considering a new rule that would allow cable consumers to use their own set-top boxes — regulation that the cable industry opposed — about 100,000 comments were posted, over the course of a few days, using language from American Commitment. Among them was another comment attributed posthumously to Annie Reeves.

One year later, 99.9% of those exact same names and addresses appeared on the FCC’s website, weighing in on an entirely different policy debate — net neutrality. They were uploaded by Media Bridge.

It seems impossible that this could have happened the way Media Bridge claimed it did. Media Bridge or LCX would presumably have had to reach all those people and convince them to sign on to the new issue. The odds of being able to reach 99.9% of 100,000 people one year later are minuscule. Even if it were possible, the odds of convincing them all to submit yet another comment, on a topic only tangentially related, seem virtually nil.

What’s more, those 100,000 comments also seemed to answer to a curious math question that had cropped up during BuzzFeed News’ analysis of the 2017 net neutrality comments. That analysis found that 94% of Media Bridge’s submissions had overlapped with the Modern Business Solutions breach. But what about the remaining 6% of submissions? BuzzFeed News has determined that almost all of them appear to have used commenters’ information recycled from 2016.

BuzzFeed News also examined the 2014 net neutrality docket, which included — in addition to yet another Annie Reeves comment, using American Commitment’s language — a strongly worded sentiment attributed to Minnesota’s then-governor, Mark Dayton. Through a spokesperson, Dayton told BuzzFeed News that he didn’t write or even know about the comment.

It was comments like these that allowed American Commitment to claim that it had “won” the original public consultation on net neutrality.

In response to BuzzFeed News’ questions, American Commitment founder Phil Kerpen said the group “is proud of its record of success and integrity in helping citizens engage in the public policy process. We’re not getting distracted by rehashed smear and innuendo campaigns.”

MEN OF LETTERS

Efforts by Media Bridge and LCX have also aroused suspicion outside of Washington.

In February 2018, lawmakers in South Carolina were “flooded” with emails opposing legislative efforts that they said would endanger the multibillion-dollar sale of Scana Corporation to Dominion Energy.

South Carolina House Majority Leader Rep. Gary Simrill found something suspicious about the correspondence. Among the emails he received was one from his good friend, William Barron. Why would Barron — whom he speaks to often and had seen within the past week — send him a form letter? He decided to try responding to the email. But when Simrill clicked to reply, the email address that popped up was one he had never seen Barron use. Perplexed, Simrill phoned Barron.

“Someone’s impersonating me,” Barron told local reporters. “It’s very discouraging, and it reeks of fraudulence.”

Simrill notified his Republican caucus colleagues. None could find a constituent who said they had really sent the correspondence, Simrill told BuzzFeed News.

The Consumer Energy Alliance — an industry group whose members include Dominion, as well as ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP — had solicited the letters. Seeking to clear its name, the group called on the South Carolina attorney general to open an investigation into what had happened.

Simrill requested an inquiry as well.

In a recent interview in his Rock Hill office, Simrill reflected on the broader implications. "It poisoned the well,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Now when you get an email ... you think, ‘Is this fake advocacy or someone who really needs something?’"

According to a source, CEA had hired Media Bridge for the letter-writing campaign, and the firm had enlisted LCX.

In response to BuzzFeed News’ questions about the campaign, CEA said it had “conducted an internal review of the data we had received from vendors and determined there were discrepancies in the submission information.”

The organization said it had decided to stop “engaging in this type of comment solicitation” until there are enough safeguards in place.

And then there was LCX’s work in Texas.

In early 2017, Texas lawmakers received a blizzard of more than 17,000 letters urging them to pass legislation that would subsidize homeschooling and private school tuition.

Allegations of foul play quickly emerged.

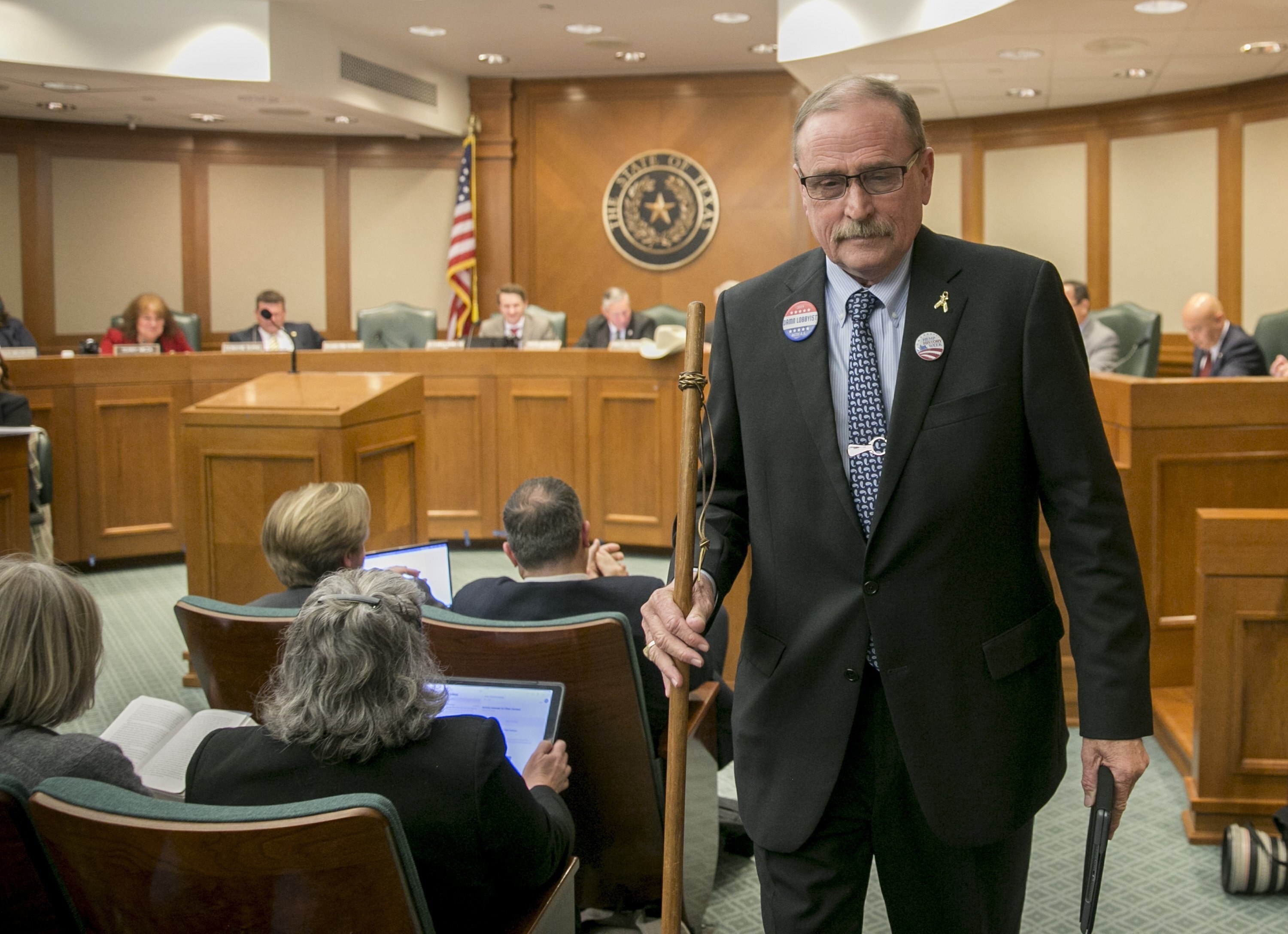

One of the formulaic letters addressed to Drew Springer, a Texas state representative, was allegedly signed by his predecessor, Rick Hardcastle — which would have been a bizarre mode of communication for two people who knew each other well. Hardcastle said the letter was fake.

“I'm not a voucher guy and everybody knows I'm not a voucher guy," he told a reporter.

After that, Springer said he called dozens of people named in the letters he’d received; none recalled sending them. Soon, another legislator referred the matter to the Travis County District Attorney’s Office, which opened an investigation, only to close it a year and a half later without making public findings.

The campaign had been organized by Texans for Education Opportunity, a nonprofit seeking to promote “school choice” policies. Each of the lawmakers that had been targeted received more than 500 letters, according to data the organization provided to the Texas Tribune.

When the Tribune started asking questions about the data, Texans for Education Opportunity referred them to its advertising vendor, LCX Digital.

LCX defended its work, saying that the high volume of letters had been generated by digital ads inviting constituents to send messages to their representatives.

The nonprofit also defended the letters in a statement to the Tribune, calling them “credible and uniquely verifiable.”

But Stacy Hock, the chair of the board, later told BuzzFeed News that her group hadn’t even known LCX existed until the allegations surfaced. The organization hadn’t hired them; it had hired Mary Cheney’s political consulting firm, which in turn had hired LCX.

The former vice president’s daughter has helped run comment campaigns since at least early 2014, when her prior consulting firm ushered at least 98,000 comments into a State Department docket in support of the Keystone XL pipeline.

After the Texas letters came under scrutiny, she defended LCX, according to documents obtained by BuzzFeed News. Hilinski had been in the industry for decades, Cheney noted, and had worked with billion-dollar companies. Plus, she said, the anomalies the Tribune had found in the data didn’t prove fraud — any mass outreach campaign was inherently bound to include a few inaccuracies.

But a review by BuzzFeed News of the same data found striking abnormalities.

The most remarkable pattern concerned the timestamps in the data. If LCX’s data is to be believed, Texans were just as likely to sign the letter at 3 a.m. as at 3 p.m. — or any other hour of the day, for that matter. But that’s not how people normally behave online. A typical person’s internet activity peaks during the most common waking hours and crashes after that.

The IP addresses listed in the data also raise questions. All 11 people listed from Keene, Texas, for instance, purportedly approved their letter-signing through IP addresses on a specific address range owned by Major League Baseball Advanced Media, which is headquartered more than a thousand miles away in New York City.

Hock told BuzzFeed News that these findings are “alarming.” She said Cheney’s firm had “launched an internal review” and was “demanding answers from LCX.” And depending on what those answers were, she said, “we will determine our future course of action, up to and including legal action.”

In a statement, Cheney added that at the time of the allegations, her organization had done “spot checks” of the data and found “nothing out of the ordinary.” However, she said, a more recent analysis “has raised some abnormalities which we have demanded that LCX explain. We are awaiting their response.”

Neither organization said it had heard back from LCX.

"COMPLETELY FRAUDULENT"

It’s not the first time people who have worked with Hilinski have been left with serious questions about what he was up to.

Hilinski founded LCX in September 2007 over breakfast with three collaborators at a scenic diner on the pier in Newport Beach, California.

In its nonpolitical work, the firm has won deals to advertise for major corporations. Its current website includes a “gallery” featuring advertisements for big-name brands such as Mazda, Toyota, and Pampers.

But one of the cofounders left the company early on, and Hilinksi’s relationship with another eventually soured. In 2011 that partner, Jeff Marder, sued over his share of the profits. The case was settled before it went to trial — but not before Marder had given a deposition full of scorching allegations against his former partner.

The company, he said under oath, was “completely fraudulent.” The way LCX made money, according to Marder’s deposition, was by misusing personal information that it had purchased elsewhere, claiming falsely that people had offered up their own details while signing up for its clients’ deals or services.

“When did you first acquire the knowledge of the fraud?” LCX’s lawyer asked.

“From the very beginning,” Marder responded.

A few moments later, the lawyer asked: “And this enterprise that was engaged in this fraudulent activity derived 100 percent of its income from this fraudulent activity?”

“That's correct.”

“It didn't have any other business?”

“No.”

In other arenas, Hilinski has made false claims about his own biography.

Hilinski has presented himself — on LCX’s website, on social media, and via press release — as having cofounded AltaVista, the famed search engine of the early internet. But there’s no trace online of Hilinski’s role. And Louis Monier, who is well-documented as being one of AltaVista’s actual cofounders, told BuzzFeed News that Hilinski “has never been involved.”

Then there was his claim in a 2016 tweet that he had “toured in Janes addiction many years ago.”

"We don't recognize that name at all," said Peter Katsis, who manages the band.

LCX’s website has also claimed Hilinski “holds an MBA from USC.” But a spokesperson for the University of Southern California said “There is no John Hilinski listed” in the degree records for the university’s Marshall School of Business.

Sitting in her living room that evening two years ago when she saw the comment in her mother’s name on the FCC’s website, Sarah Reeves logged on to Facebook and posted angrily in all caps: “WOW IT SURE IS GOOD MY DEAD MOTHER HAD SOMETHING TO SAY ABOUT NET NEUTRALITY ISN'T IT.”

She and her sister tried to figure out how to get their mother’s comment removed from the site, but the FCC doesn’t provide a way to do that. "I think that was one of the worst things for me," she told BuzzFeed News.

She had also found a comment in her own name, which BuzzFeed News has identified as among Media Bridge’s uploads. Unlike her mother, Sarah Reeves did have opinions about net neutrality — she was strongly in favor of it. But this comment espoused exactly the opposite stance.

"By the end of the day, I was pretty defeated," she said.

The repeated appropriation of her mother’s name still frustrates Sarah Reeves. "It's too easy to post fraudulent comments," she said. "It gave us this impression that it didn't matter how we actually felt." ●