Let’s be clear and state three facts.

First, anyone can get monkeypox.

Second, the current outbreak is overwhelmingly concentrated among men who have sex with men.

And third, a growing body of evidence and data suggests that sex among these men is the primary means through which monkeypox is presently spreading.

While it’s true that there are other ways the virus can be transmitted, recognizing and reporting these facts is not anti-gay or anti-science, and neither is targeting advice to members of this community given they are the ones who are presently most at risk.

More than 31,000 people around the world have contracted monkeypox — almost a third of them in the US, where the Biden administration has declared a public health emergency. Every state but Wyoming has detected at least one case.

And yet, whether through fears of perpetuating stigma or just general squeamishness about using the words “anal sex” in headlines, health officials and the news media have appeared extremely hesitant in speaking frankly about sex to who is most at risk. In Washington, DC, officials even broadened vaccine eligibility to include people of all genders in part due to a desire to “[destigmatize] the individuals who may need a vaccine.”

Public fears have also been stoked about catching monkeypox through trying on clothes in stores or via rats in the sewers by medical experts who have branded themselves online as pseudo COVID-turned-monkeypox influencers. (For the record, experts say neither of these scenarios are something to be concerned about.)

All this, experts say, may actually be doing more harm than good, according to Angie Rasmussen, a virologist at Canada’s center for pandemic research, the Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization at the University of Saskatchewan.

“The discourse around this has become so exhausting: watching my friends who are queer health advocates trying to get info and vaccines/treatments to people at risk are contending with armchair experts and clout chasers screaming, ‘AIRBORNE!’ and wringing their hands about their kids getting monkeypox at kindergarten,” Rasmussen wrote in a message to BuzzFeed News. “It’s doing great harm to the people who are most at-risk NOW.”

So what does the data say about who is getting monkeypox?

The people getting infected with monkeypox right now are overwhelmingly gay, bisexual, or queer men. And when we say overwhelmingly, we mean it.

In an update last week, the WHO said that among the more than 8,400 cases with known data on sexual orientation, 97.2% were men who have sex with men. Furthermore, of the almost 6,000 reported types of transmission, 91.5% of cases stemmed from sexual encounters.

“With the exception of countries [in the] areas of West and Central Africa, the ongoing outbreak of monkeypox continues to primarily affect men who have sex with men who have reported recent sex with one or multiple partners,” the WHO stated. “At present, there is no signal suggesting sustained transmission beyond these networks.”

In a New England Journal of Medicine study published last month that examined more than 500 monkeypox cases in 16 countries, 98% of patients were gay or bisexual men. Another study published July 28 in the British medical journal BMJ involved 197 monkeypox patients at a London sexual health clinic. All but one of these men — and they were all men — identified as gay, bisexual, or a man who has sex with men.

In the US, the data is the same. CDC data from July 25 shows that 99.1% of cases are among patients assigned male at birth, and 99% of these men reported recent sexual contact with another man.

To explain the concentration of monkeypox among these men, experts say it’s important to think of them not as individuals, but as communities or networks of people who are coming into close contact with each other.

In other words, the virus hasn’t become more contagious — it’s just made its way into a new network of people.

“I think it’s really about the virus being able to exploit network effects and close contacts between individuals,” said Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins University Center for Health Security, “and use amplification events like raves — where many people might have had multiple close contacts with multiple partners, and some of them anonymous — and that allowed the virus to spread in a way that it really hadn’t had the opportunity to do so before.

“It probably always had that potential,” Adalja said. “It just needed to get into a network like this.”

What does this data tell us about the way monkeypox is spreading?

Per the CDC, there are three main ways you can contract monkeypox: direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected person; touching contaminated surfaces, objects, or fabrics (i.e., fomites); and contact with respiratory secretions like mucus (aerosols).

But given this current outbreak is spreading so predominantly among these networks of men who sleep with each other, experts say that prolonged skin-to-skin contact during sex is what is driving most of these cases.

“Based on the data we have, it looks pretty convincing to me that sex is playing a dominant role in the spread of monkeypox, together with the fact that perhaps these patients had sex with multiple partners,” Gerardo Chowell, an epidemiologist at Georgia State University School of Public Health in Atlanta, told BuzzFeed News. “And that’s probably why we haven’t seen as many cases among heterosexuals.”

Rasmussen said that if fomites and aerosols were huge drivers of monkeypox, the data would show a lot of cases occurring outside of gay men, bisexual men, or men who have sex with men (GBMSM). “Not all transmission is associated with sex, but most is,” Rasmussen said. “If this were transmitted more commonly by aerosols, fomites, or incidental contact, we’d see way more household transmission and spread into the larger community.

“GBMSM don’t live in isolation: they have kids, families, coworkers. We’d see more cases in those people if the spread weren’t driven primarily by sex,” Rasmussen added. “Though again, there is some nonsexual transmission occurring, just not that much.

“It would likely spread among heterosexuals as well if it established itself within those sexual networks.”

For its part, the Department of Health in New York City, which has tallied more than 2,000 cases of monkeypox, lists the three possible methods of transmission on its website but first states plainly: “In the current outbreak, the monkeypox virus is spreading mainly during oral, anal and vaginal sex and other intimate contact, such as rimming, hugging, kissing, biting, cuddling and massage.”

How does monkeypox spread through sex?

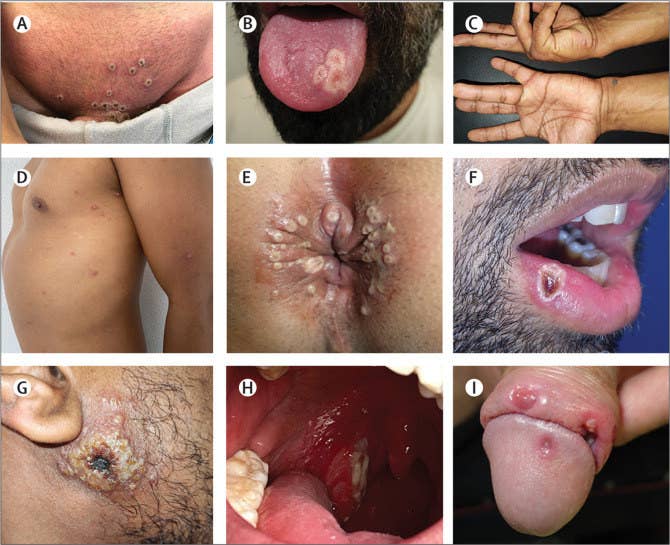

Experts believe it takes much more than a light brush of the skin or a handshake with an infected person in order to catch monkeypox; what’s required is consistent rubbing against a person who has rashes, scabs, or lesions, or said person’s bodily fluids. The most obvious and easy way for this to occur is during sex, but dancing or grinding up against a shirtless person at a circuit party also poses some risk.

The role of sex in spreading monkeypox appears to have been evident for several years now.

This current outbreak of monkeypox seems to be connected to one identified in 2017 in Nigeria, which appears to have now spilled out globally.

At the time, perplexed scientists there had questioned why so many men in their 20s and 30s were getting sick and were showing rashes not on their faces and extremities, but rather on their genitals. They soon discovered many of these patients had demonstrated high-risk sexual behaviors that included sleeping with multiple partners and with sex workers.

“Although the role of sexual transmission of human monkeypox is not established, sexual transmission is plausible in some of these patients through close, skin-to-skin contact during sexual intercourse or by transmission via genital secretions,” Dimie Ogoina, professor of medicine and infectious diseases at Niger Delta University, wrote with colleagues in a 2019 medical journal.

Further studies related to this current global outbreak have given further strength to this idea, Ogoina wrote in a new piece of analysis published in the Lancet medical journal just last week.

Ogoina made special mention of another Lancet study published earlier this month by scientists in Spain of 181 monkeypox patients there, 92% of whom were GBMSM. The researchers found “significantly higher” viral loads, or amounts of the monkeypox virus, on swabs of lesions on patients than in their respiratory samples.

Furthermore, more than three quarters of the patients had lesions around their anus or genitals, while more than 40% had lesions in their mouth or around it. Forty-five patients were also suffering from proctitis, or inflammation of the lining of the rectum, and all but four of these men had engaged in anal-receptive sex.

The researchers theorized that anal sex might damage the outer layer of body tissue, enabling blood entry of the virus.

“Additionally, mild trauma in the pubic, inguinal, and perianal regions during sexual intercourse might cause local vasodilation and a higher density of skin lesions in that particular region,” they wrote.

“All these findings together suggest that close skin-to-skin contact during sex is probably the dominant transmission route in the current outbreak,” Andrea Alemany, one of the study’s authors, told BuzzFeed News.

There is even some evidence that monkeypox might be spreading via semen, with another Lancet study by Italian researchers finding infectious virus samples in semen from one patient 19 days after his symptoms first began.

As Jeffrey Klausner, a professor at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine, and Lao-Tzu Allan-Blitz, a physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Boston Children’s Hospital, summarized in a Medium post published on Saturday, “Taken in context, the temporal and anatomic association with various sex practices, the high prevalence of sexual risk behavior among patients with human monkeypox, and the in vitro infectivity of human monkeypox DNA isolated from semen strongly suggest that human monkeypox is transmitted through sexual activity.”

So is monkeypox an STI?

Even though data and studies suggest monkeypox is overwhelmingly spreading via sex in this outbreak, researchers aren’t yet comfortable classifying it as a sexually transmitted infection, or STI, which would mean it’s being transmitted via the close contact or exchange of fluids that only really happens in sex.

Alemany, one of the researchers on the Spanish study, said this was because of what scientists know about the ways the virus has previously spread. There is also presently a minority of patients, including a few children, who have become infected without having sex.

“Direct skin-to-skin contact has promoted the spread of the disease through sexual networks in the current outbreak,” Alemany said. “However, monkeypox can be transmitted through other forms of prolonged close contact, and through respiratory droplets and fomites, which have played an important role in previous outbreaks. More research into their role in the current outbreak is required.”

The WHO last month convened a panel of STI experts to discuss this potential classification, but these scientists decided against it at this stage.

“They’ve concluded this is clearly transmitted during sex, so they’re comfortable in describing this as sexually transmittable, but they have not yet felt able to reach a conclusion that this is an STI,” Andy Seale, a WHO adviser on sexually transmitted infections, told reporters.

Still Klausner and Allan-Blitz have said, “The transmission dynamics of human monkeypox, at least across the United States and Europe, appears to be highly consistent with a sexually transmitted infection.”

There would be both positive and negative ramifications from labeling monkeypox as an STI, according to experts.

Stigma might discourage people from seeking treatment or alerting partners, but it also might cause others in the public to downplay the threat.

“The danger in labeling something like monkeypox as a sexually transmitted infection is that a lot of people switch off,” Matthew Hamill, an infectious disease professor at Johns Hopkins, told Gothamist. “Because they think, ‘well, that’s nothing to do with me. That doesn’t apply to me.’”

But it could also help high-risk groups make informed decisions about their sexual activity that could help to reduce the number of cases, perhaps by reducing their number of partners (as the WHO has temporarily advised). It might also allow some people to access free testing or reduce the amount of time they may need to spend isolated from others and unable to work.

“In lieu of vaccination, we have to think about harm reduction, and we do harm reduction for many infectious diseases,” said Adalja at Johns Hopkins. “I think it’s really important to give people tools, to tell them that having a new sexual partner right now is something that’s a risk factor for monkeypox, and maybe thinking about decreasing the number of partners temporarily until you're vaccinated or immune, or making sure you exchange information with people so it makes contact tracing easier.”

Will all this lead to stigma against queer men?

Wary of perpetuating anti-gay stigma, health officials have struggled to communicate the twin ideas that while anyone can get monkeypox, it’s GBMSM who are currently most at risk.

“It is a very difficult message to put across,” Rosamund Lewis, technical lead for monkeypox at the WHO Health Emergencies Program, told reporters.

It’s important to tailor public health messaging to those most at risk, experts believe, but that will inherently cause some level of public stigma.

“The labeling of the outbreak as a disease among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men is certainly both necessary from a harm reduction perspective, but is also a stigmatizing message at the same time,” said Jason Farley, director of Johns Hopkins’ Center for Infectious Disease and Nursing Innovation.

Rasmussen, the virologist in Canada, said public health authorities need to give frank and practical advice focused on harm reduction, such as information on safer sex, that targets queer men. At the same time, experts need to leave open the possibility that their recommendations might need to be tweaked again if the virus spreads into other sexual or social networks.

“What’s challenging is communicating that while this not a ‘gay disease,’ our limited resources need to go to the people at the highest risk, currently GBMSM,” Rasmussen said. “And it’s also important to communicate the risk is highest with sexual activity without shaming the queer community that has already been profoundly harmed by medical stigmatization.”

And while well-meaning people may want the media or public health authorities not to focus on the LGBTQ community for fear of spreading stigma, allowing the virus to spread may cause much greater harm.

Gettysburg College history professor Jim Downs argued in a piece published in the Atlantic this weekend, titled “Asking Gay Men to Be Careful Isn’t Homophobia,” that officials should not “tiptoe” around how the virus is spreading and instead state plainly that queer men need to refrain from high-risk sex until they are fully vaccinated.

“As a gay man and a historian of infectious disease, I know about the harm that comes when public policy becomes infused with homophobia,” he wrote. “Yet protecting gay men from discrimination and stigmatization today does not require public-health officials to tiptoe around how monkeypox is currently being transmitted.” ●