SAINT CHARLES, Missouri — Michael Johnson was finally getting his day in court.

Best known by his screen name, Tiger Mandingo, the black, gay, HIV-positive college wrestler with a chiseled body had been accused of infecting two men with the virus and of “recklessly” exposing four others to it.

Under Missouri law, HIV-positive people must tell all their sexual partners that they are infected, even if they practice safe sex. Johnson was accused not merely of keeping his HIV status to himself, but of willfully lying to his partners, telling them he was HIV-negative before engaging in what the prosecutor would call the most “dangerous” form of sex: ejaculating without a condom into the rectums and mouths of his sex partners.

As his lawyer tried to negotiate a plea deal, the 23-year-old Johnson rejected the idea, even after a friend visited him in jail and begged him to reconsider, and even though Johnson said he had spent months in solitary confinement, not even allowed to go to church. He was innocent, he said, and had confidence in the American criminal justice system. So on May 11, he was in St. Charles County court, where the judge and the lawyers began to choose the 12 jurors who would decide if he would spend the rest of his life in prison.

No one had shown up to support him. His own mother wasn’t there; she would arrive late and leave before his trial ended. His only ally that morning was his public defender, Heather Donovan, a petite white woman in a gray suit, and she stood up in front of the pool of potential jurors and told them that her client was...guilty until proven innocent.

Amid groans in the courtroom, the judge, Jon Cunningham, reminded Donovan that she’d meant to say the opposite: that her client was innocent until proven otherwise.

Things never got better for Johnson, who has become one of the most highly publicized targets of America’s controversial HIV laws, which make it a crime for HIV-positive people to have sex without first disclosing that they have the virus. When actor Charlie Sheen announced that he is HIV-positive last month, he said that at least two of his sexual partners had been “warned” about his health status. But another of his sex partners came forth to say the actor never told her that he has HIV, potentially opening him up to prosecution under California’s law.

Many prosecutors defend HIV laws as offering just punishment for behavior that can help transmit the virus. But critics say the laws unjustly place all responsibility on the person with the virus: While Johnson faced up to life in prison, his partners bore no legal liability, even though they all willingly engaged in unprotected sex acts during casual hookups with “Tiger.”

The soft-spoken former university student had shown up to court in a blue shirt and a bright red tie, but standing trial was his black, ejaculating, HIV-positive penis.

More fundamentally, AIDS advocates say, the laws are outdated and harsh. If decades-long sentences ever were appropriate, they say, they aren’t anymore, given the tremendous medical advances in HIV care. Indeed, many epidemiologists and AIDS advocates say the laws — which single out HIV — can actually fuel the epidemic by making people afraid to get tested and treated, and by fostering the dangerous belief that only the HIV-positive person is responsible for preventing transmission of the virus.

But what propelled Johnson’s case into headlines as far away as Australia was the volatile combination of race and sex epitomized by his own screen name, Tiger Mandingo. Many of Johnson’s sex partners — including four of the men he was charged with exposing to HIV — were white. And almost every news account featured photos that Johnson had posted on social media of his dark-skinned, muscular, and often shirtless torso.

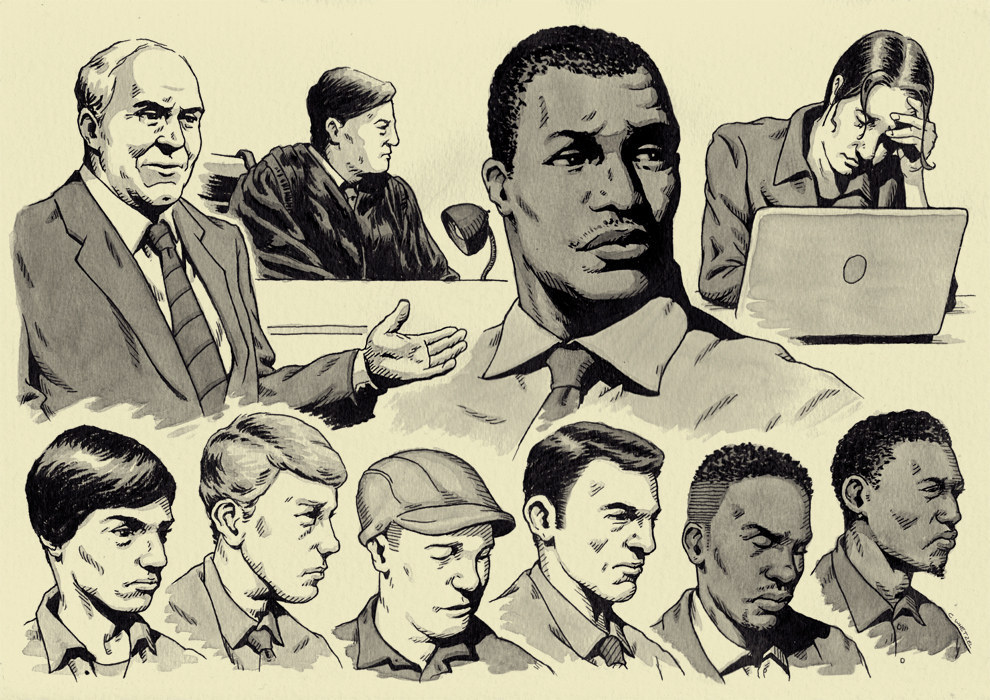

That lurid fascination with Johnson’s black body carried over into his trial. Arrested and charged in an overwhelmingly white community where anti-gay beliefs are widespread, the gay, black “Tiger” never stood a chance. Over five days, as a procession of sex partners and medical experts, as well as Johnson himself, testified, what unfolded was a courtroom drama that on the surface pitted an aggressive prosecutor against a hapless public defender, but that in a deeper sense pitted Johnson against America’s deeply entrenched attitudes about race and sexuality.

Characterized by his sexual partners as being “very large,” “too tight” for condoms, and too big to fit in a mouth “due to his large size,” Johnson/Tiger’s penis was described in unusually graphic and at times almost absurd detail in police reports and later on the stand. It would even be shown to jurors in still images from a sex tape that he and one of his partners made. The soft-spoken former university student had shown up to court in a blue shirt and a bright red tie, but standing trial was his black, ejaculating, HIV-positive penis.

The Jury

Of the 51 potential jurors, only one appeared to be nonwhite — a female, African-American retired nurse — and all identified as straight. Most looked to be in their fifties or older. During questioning, about half of the would-be jurors said being gay was a “choice.” Only a third agreed that being gay was “not a sin.” No potential juror acknowledged having HIV. All said they believed HIV-positive people who do not tell their sexual partners that they have the virus should be prosecuted. When asked, not a single person said they had any distrust of the police. (The quotations from this trial are from the reporter’s notes. Following directions from the court, BuzzFeed News did not record the proceedings, and the court has declined to make transcripts available.)

When the prosecutor, Philip Groenweghe, made arguments from notes, he confidently lifted his eyes from his papers to make eye contact with whomever he was addressing. But much of the time, his arguments were so polished, and he seemed so confident in them, that he spoke eloquently and persuasively without notes. His hands went in and out of his pockets as he emphasized points, and he grabbed his lapels or took his glasses off with dramatic effect. He stalked the courtroom, never asking the judge for permission to approach the bench. He would drop his voice to sound reasonable while addressing jurors, but he sometimes yelled and jabbed his finger at witnesses.

Donovan, who appeared many years Groenweghe’s junior, clutched her notes, the papers sometimes shaking. Donovan routinely asked Judge Cunningham for his permission to approach the bench (as did the female prosecutor), and she rarely made eye contact with anyone. When she spoke, she often stammered and stumbled over her words. (Donovan did not respond to requests for comment.)

Groenweghe was backed up at all times by another attorney, Jennifer Bartlett, and an omnipresent paralegal, along with a rotating cast of four or five police detectives, assistants, specialists, and a victim’s advocate sitting right behind them in the first bench of the galley. All were dressed in somber business suits. Groenweghe’s boss, Republican St. Charles County Prosecuting Attorney Timothy Lohmar, is a rising attorney from a local political dynasty (the trial took a recess for the funeral of his father, a former judge).

Meanwhile, save for an assistant who would come into the courtroom once or twice a day for a few minutes to deliver papers, and who was often dressed in casual jeans and a blouse, public defender Donovan was alone — except for her client, whom she often did not acknowledge, even neglecting to greet him most times he was led into court.

Judge Cunningham, who had a soft, lilting voice, presided over the courtroom with a light air. He didn’t interject, and he would often pause in contemplation before overruling or sustaining an objection. But he usually ruled against Donovan.

Weeding out whom he didn’t want on his jury, Groenweghe repeatedly asked the kinds of questions (and heard the kinds of answers) about homosexuals one can no longer ask about black people outright. A handful of the younger potential jurors said positive things about gay people, but many used words such as “sick,” “wrong,” and “immoral.” Groenweghe later told BuzzFeed News he was trying to weed out anyone who was anti-gay — but none of the younger potential jurors made it onto the jury.

Later, during the actual trial, Groenweghe’s balding head and thick neck would turn almost red as he described the “lifestyle” of homosexuals. When talking about HIV and gay sexual acts, he spat out the words “semen,” “blood,” and “mucus membrane.” (He later said he was being “precise” about medical terminology.) But he spoke relatively evenly for nearly two hours during jury selection, using his time to build the central argument he wanted his eventual jurors to buy — and to screen out potential jurors who might not buy it: Whenever HIV-positive people don’t tell their sexual partners that they’re positive, that’s a crime, even if their partners didn’t ask or were promiscuous.

Donovan spoke for only about 10 minutes during jury selection, and brought up prejudice and racism rarely, such as when she asked potential jurors if they would have a problem talking about interracial gay sex acts.

When the jury was finally selected, it was made up of four white men, seven white women, and the black retired nurse, all proclaiming to be HIV-negative and straight. A couple of the jurors may have been in their forties, but most appeared to be in their fifties or sixties.

The Accusers

Once the trial began, it quickly became clear that the State of Missouri v. Michael L. Johnson was not a case of “he said versus he said,” but of “he said versus they said.” Each of Johnson’s six sex partners called to the stand testified that they asked Johnson before they hooked up if he was “clean” or STD-free, and that he'd assured them he was.

But their testimony occasionally contradicted what they had initially told police, sometimes on crucial points. The jury never heard about several of these discrepancies, because Donovan sometimes failed to pounce on them during cross-examination, and when she did, she was often overruled.

Even when the accusers’ testimony wasn’t contradictory, it revealed the complicated, murky decision-making that happens in sexual hookups. The sex partners all said the sex was consensual — they willingly engaged in sex that could transmit HIV — yet they often used passive language to describe how it was they’d come to have unprotected sex with Johnson’s “huge” penis on the black sheets of his Lindenwood University dorm room.

Dylan King-Lemons, a lithe young blonde man, was the person who first pressed charges against Johnson, prompting the prosecution to search for other alleged victims. And his accusation was one of the most serious: Johnson had not merely exposed him to HIV — Johnson had actually infected him.

It was not a case of "he said versus he said," but of "he said versus they said."

Lemons testified that he began his sexual relationship with Johnson on Jan. 26, 2013, when they were both students at Lindenwood’s suburban campus west of St. Louis. Lemons said he was regularly tested for HIV, always asked his partners if they were HIV-positive, and wanted to use a condom with Johnson. But, he testified, Johnson told him that he was HIV-negative, that the condom was “too tight and too small,” and that “they don’t make condoms in his size.” So, Lemons said, he agreed to have unprotected sex in the “traditional female role” and said that Johnson ejaculated inside his anus.

About two weeks later, Lemons testified, he went to Mercy Hospital with severe stomach pains. He was hospitalized twice, for a total of 14 days, according to his testimony and that of his attending physician, Dr. Otha Miles. Lemons was eventually diagnosed with gonorrhea and HIV.

The timing of what was said to be Lemons’ “HIV flu,” which can sometimes occur shortly after someone is exposed to the virus, and the fact that they both had gonorrhea formed the circumstantial basis of evidence tying Lemons’ diagnoses to Johnson’s. But no scientific tests, such as genetic fingerprinting of the virus, were performed to determine if Lemons’ strain of HIV was the same as Johnson’s.

In his opening statement, Groenweghe said Lemons knew Johnson had to be the one who infected him because he was the only person he’d had sex with in the prior 11 months. On the stand, Lemons also testified that he hadn’t had sex with anyone else in nearly a year — meaning he wouldn’t have had sex with anyone but Johnson from January or February of 2012.

But when he first went to police, Lemons said that he “had been able to narrow it down between two people” — Johnson and another sexual partner, a woman — “because of the time frame” his doctor had given him for the date he was likely infected, six months before his hospitalization. His relationship with the woman, he told Detective Stepp, lasted “from May 2012 until the end of November 2012.” He told Stepp that he had had sex with a total of six people in his life and that a state public health officer told him that all of them except Johnson had tested negative for HIV.

In the police report, a woman described as Lemons’ “best friend,” who was questioned separately, told Detective Stepp she believed Lemons had been dating a third person, about “8.5-9 months prior” to Lemons getting sick. It could not be determined if this person was one of the five people the state public health officer said had tested negative. According to the police report, the friend said that both the other people Lemons had been seeing were “very promiscuous.”

Lemons declined to comment, as did one of his two other sex partners. The second one could not be reached, and Lemons’ friend did not respond to requests for comment.

In her cross-examination, Donovan did not press Lemons on the discrepancies between his testimony and what he initially told the police, nor did she mention his other sexual partners — points that bear on Lemons’ credibility and cut to the very heart of the allegation that Johnson was the person who infected Lemons. (Later, she tried to ask his physician if Lemons had had sex with an “old friend,” but Groenweghe objected, successfully, on grounds that the doctor wouldn’t know who his sexual partners were.) In court, she did not point out that the prosecution offered no scientific evidence that Lemons’ and Johnson’s viral strains matched.

In the police report there is a passage in which Lemons seems afraid that the tables will be turned and that he, the accuser, might become the accused. After Lemons finally got out of the hospital, he told Detective Stepp, he met up with Johnson and told him he was HIV-positive. They then had sex again, and again without a condom. Detective Stepp wrote:

I asked Lemons if he was forced to have sex and if he thought he was raped. Lemons stated that he was not raped and he doesn’t want [Johnson] to “go down as a rapist.” Lemons proceeded to say, “I don’t think I was raped but I don’t want this to come back on me. I told him I was HIV positive and highly contagious.” Lemons advised that he told [Johnson] that he wasn’t going to fight having sex but it would be very stupid if they did. Lemons advised that he wanted to have sex but he didn’t want to infect [Johnson]. Lemons said several times that he wanted to be clear that he didn’t feel he was raped but he wants me to know he warned [Johnson] of his HIV diagnosis.

At trial, Lemons testified that he is now engaged to marry a man who is HIV-negative and that they have never had sex — not even with condoms — out of fear of transmission. Lemons also testified that without health insurance, his hospitalization plunged him $100,000 into debt and that he had to declare bankruptcy. A search by BuzzFeed News of online court databases such as PACER turned up no record of him having filed bankruptcy, and Groenweghe told BuzzFeed News, “I didn’t check bankruptcy records.”

Another witness, Andrew Tryon, was a tall, thin, blonde Lindenwood University cheerleader. He and Johnson consensually filmed their sexual encounter, and stills from the video were printed and handed out to to the jury. Groenweghe said they showed Johnson topping Tryon, ejaculating on his back, then using his fingers to feed Tryon what Groenweghe called “HIV-infected semen.” When the jurors looked at the stills, their faces were stoic and impassive.

On the stand, Tryon testified that the sexual encounter he’d had with Johnson matched what the tape showed. But in his initial police report, Tryon describes having sex with Johnson on three different occasions, and none matched what the video showed. For example, in cross-examination, Donovan got Tryon to admit he’d first described jacking Johnson off before swallowing his semen, not having Johnson ejaculate on his back, as the video showed.

The testimony revealed the complicated, murky decision-making that happens in sexual hookups.

Wiry and pale, Charles Pfoutz took the stand. He spoke in a clipped and breathless manner, and the portion of his head not covered by a hat looked shaved. His charges against Johnson were not filed until he’d been in jail for a year and a half, right before the trial. Pfoutz admitted to prosecutor Jennifer Bartlett that he had a previous criminal record, having pleaded guilty to a burglary in November 2009.

Pfotuz testified that he’d told Detective Stepp that he got tested regularly for HIV — every other month, he said. Yet he also testified that he’d had unprotected receptive intercourse with “Tiger Mandingo” — at that point he didn’t know Johnson’s real name — the day they met on Jack’d, a gay hookup app similar to Tinder.

In her cross-examination of Pfoutz, Donovan had her most effective moment. She lashed Pfoutz to his previous deposition, in which he had said under oath that when he’d first found out he was HIV-positive he’d told medical personnel that he’d been having sex with only one man — and it wasn’t Johnson. Pfoutz said he’d been having sex since 2007 with that man, and that they were monogamous. Donovan’s cadence sped up while parrying with Pfoutz, whose eyes got wider and speech got faster, in one of the only times in the trial in which Donovan looked the person she was addressing in the eye. Pfoutz looked shaken when he left the stand, and the next recess was the only occasion when chatter among court observers revealed any sense that the defense had discredited a witness.

The credibility of Johnson’s partners was not on trial.

Filip Cukovic, a slim Serbian exchange student, testified that he found Johnson “unusual because he was black,” and there were only white people in his home country. Johnson was charged with exposing him to HIV after having anal intercourse with and without a condom before ejaculating on the side of Cukovic’s head. Detective Stepp wrote that after being with Johnson, Cukovic was “scared to even touch himself.”

Christian L. Green, a skinny African-American man, testified in a soft-spoken voice that he bottomed for Johnson, without ever considering using a condom: “After I asked him if he was clean, I didn’t think about it.” Montel Moore, another slim black man, testified that although he bottomed for Johnson without protection, he pushed Johnson off before he could ejaculate inside him.

Moore initially told police that he “he did everything opposite that he would normally do” that night, including that he “doesn’t have random sex with strangers, is usually not the receiver of anal sex, doesn’t perform oral sex, and always wears a condom.” According to the police report, Moore also said that while having sex with Johnson, his

roommate came home early and walked into the dorm room. Moore further stated that “Tiger” quickly jumped into the bathroom. Moore explained that his roommate is also gay and that they had been involved in a relationship last year. Moore advised he thought he had to deceive his roommate to avoid any drama. Moore explained that he had told his roommate that he had invited “Tiger” over to surprise him with a “three-way.”

But the credibility of Johnson’s partners was not on trial — not as to whether they may have exposed themselves to HIV through other sexual encounters, or if they were to be believed about what they were saying about Johnson, and least of all if they bore any responsibility for the sex they consented to. Groenweghe kept the focus on whether or not Johnson told them he had HIV.

The Doctors

The doctors and medical experts who took the stand provided evidence that clearly hurt Johnson’s case. But when two of them tried to testify that HIV is a manageable disease — that with current therapies a person with the virus can expect to live almost as long as someone without it — Groenweghe objected vociferously. By doing so, he managed to curtail a crucial point: HIV today is nothing like the death sentence it was in 1988, when Missouri passed the law that Johnson was on trial for breaking.

Those medical personnel who met and examined Johnson personally — nurse practitioners Marianne Adolf and Kelly Martin, and Missouri Department of Health epidemiologist Frank Lydon — testified that Johnson had indeed tested positive for HIV before he had sex with the six partners, and that he’d been treated for gonorrhea at least three times.

They also confirmed that Johnson acknowledged his HIV infection and that he had received HIV counseling several times and been repeatedly told that failing to disclose was a felony. According to a police report, a health department document noted that Johnson was not informing his partners of his sexually transmitted infections.

Groenweghe asked Adolf, a plump, middle-aged white woman with thinning straw hair and glasses, to describe how a condom could be blown up like a balloon until it was big enough to fit over someone’s head. This was designed to expose as bogus the excuse Tryon and Lemons said Johnson gave — that he was “too big” or the condoms were “too tight.”

But the most damaging testimony came when Martin said Johnson told her he wasn’t sexually active when he clearly was, a lie that prosecutor Groenweghe hammered home.

Dr. Otha Miles, an African-American doctor at Mercy Hospital who treated Lemons and testified for the prosecution, called HIV a “terminal” disease. But the defense’s medical witnesses — Dr. David Hardy of UCLA Medical School and Dr. Rupa Patel of Washington University in St. Louis and Barnes-Jewish Hospital — strongly disagreed that HIV is a “terminal” disease when treated properly.

Patel testified that most people are afraid of HIV because of stigma and what they learned in the 1980s. But, when treated properly by taking as little as one pill a day, she said, “life expectancy should be normal.” She added that some patients need to see a doctor only every six to twelve months.

Among HIV experts, Patel's and Hardy’s views are anything but controversial. A 2013 study estimated that a person in the United States or Canada who contracts HIV at age 20 and gets treatment “is expected to live into their early 70s, a life expectancy approaching that of the general population.” Even if Johnson had transmitted HIV to Lemons, Hardy's and Patel’s expert opinions were that it was the transmission of a treatable disease, and not of a death sentence.

But when Patel attempted to compare HIV to other chronic medical conditions — arguing, for example, that HIV can be easier to treat than diabetes — Groenweghe successfully interrupted her arguments by objecting that she was trying to add unsolicited information to a yes-or-no question. Then, during cross-examination, Groenweghe attacked Patel, yelling, “You’re supposed to be a scientist!” Who, he demanded, did she work for: the public defender paying her, or objective science? Groenweghe pointed out that Dr. Patel had not examined Johnson personally and he accused her of not having reviewed all of Johnson’s medical records.

Ultimately, he turned his ire on the public defender herself, accusing Donovan of withholding information from her witness. Donovan objected loudly, saying she “resented” Groenweghe’s accusations.

Judge Cunningham called the lawyers to the bench. From about 20 feet away, Donovan could be heard crying, telling the judge she was doing the best she could and working with what she had, and that she was being personally attacked by Groenweghe. Her crying got louder as she said, “You are going to need to have a new trial in a few minutes because I am going to be disqualified.”

Donovan then stormed out of the courtroom, abandoning an incredulous-looking Dr. Patel on the stand — and leaving Johnson looking bewildered.

When Donovan came back in, her eyes still puffy, the bailiff brought her tissues. The judge called a recess for 15 minutes, which stretched to nearly an hour until Donovan returned.

The Accused

On the last day of testimony, Johnson took the stand in his own defense. His own mother and two of his friends said they didn’t want him to do so. He has learning disabilities and by his own account does not read or write very well. When Donovan asked him how he’d gotten to college, intending for him to explain his athletic scholarship, he answered her literally, saying he’d gotten to Lindenwood University by taking a bus.

But he spoke calmly, deliberately, and slowly, testifying that he had disclosed his HIV status to each of his six of his partners prior to having sex and that he remembered doing so with each one. Still, while the jury never got to see how some of Johnson’s accusers contradicted what they said in police reports, the jury saw Johnson appear to contradict himself — on video.

Groenweghe played a clip of Johnson being interviewed (without a lawyer present) by Detective Stepp in 2013. Johnson and Stepp, both in the courtroom, silently watched themselves onscreen. In the clip, Detective Stepp hands Johnson a photo and asks who it is. Johnson says he doesn’t know.

Groenweghe pounced. The photo showed Lemons. How could Johnson not know when questioned in 2013 who Lemons was — yet on the stand in 2015 remember that he had disclosed to him? He must have been lying then, or lying now, or both.

Groenweghe then played an audio tape of Johnson in jail talking with Meredith Mills, who befriended Johnson when he played soccer with her stepson and has remained close to him. On the tape, Johnson said it was difficult to tell her something. The clip was very short and the context unclear, but Groenweghe said the exchange was about how hard it was coming out to Mills as HIV-positive. Mills and Johnson later told BuzzFeed News that he was speaking about coming out as gay.

By the time he left the stand, Johnson had admitted he was only “pretty sure” he had disclosed.

The Verdict

Groenweghe smiled throughout the last day, his eyes twinkling as he delivered his closing arguments and recapped one piece of evidence against Johnson’s credibility after another: Johnson contradicting himself on video and audio, Detective Stepp’s testimony about how he investigated Johnson, the testimony of the medical personnel who said they explained to Johnson that not disclosing would be a felony several times, and the collective testimony of all six men who said Johnson had told them he was not infected.

Groenweghe warned the jurors that they needed to keep the public safe from Johnson — who roamed the world with a “calling card” of “HIV with a tint of gonorrhea mixed in" — by convicting him and locking him up forever.

In her closing statement, Donovan repeated that her client had testified that he had told his partners that he was HIV-positive, and she made points she had been unable to get in during her cross-examinations. For the most serious charges of HIV transmission, she highlighted Lemons’ contradictory stories on the stand and in previous statements, and she said he altered the date when he’d had an HIV test — all of which, she said, “bring reasonable doubt into when Mr. Lemons contracted HIV and from whom.”

Regarding Pfoutz, she said he didn’t even approach the police until more than a year after he’d said his sole sex partner was someone other than Johnson.

That evening, just about two hours after closing arguments were finished, the jurors signaled that they had reached a conclusion. They found Michael Johnson not guilty on all charges involving Pfoutz.

But, they found Johnson guilty of recklessly transmitting HIV to Lemons and of exposing or attempting to expose the four other men to HIV.

The Jury’s Sentence

The following morning, the jury convened to hear evidence and arguments on what sentence they should give Johnson. For the transmission conviction alone, the minimum was 10 years, while the maximum, according to the statute, was “30 years to life.”

“What you have seen and heard so far is only the tip of the iceberg,” Groenweghe said in his opening statement. “Now we can tell you more.”

Groenweghe went on to say that although the charges were about the six people who’d given testimony, the jury was going to hear about 32 more sex videos made with other sex partners. They would also hear about people who had come forward after news broke about “Tiger Mandingo” but who had declined to press charges against Johnson, including an unnamed married man who, Groenweghe said, didn’t want to press charges because he didn’t want his wife to find out.

Christine King-Lemons, the mother of Dylan King-Lemons, testified for the prosecution at sentencing and told the jury to send Johnson away for life in prison. “Dylan’s diagnosis is a life sentence without parole,” she said through tears. “So I ask each of you: Why does Michael Johnson deserve any less?”

Mills, whose stepson had played soccer with Johnson, was the only witness to speak on his behalf. Mills described him as a “gentle giant” who had become a member of her family after he’d been befriended her stepson. Johnson, she added, was very good with her young daughter, who has severe emotional needs.

But on cross-examination, Groenweghe asked her why, after Johnson had been arrested and was in jail, she hadn’t instructed him to tell officials whom he had slept with. She said she knew her phone calls were being recorded and might be used against him — as they were. Groenweghe accused her of not caring about the mothers of the other affected young men.

Johnson’s mother, Tracy Johnson, did not testify.

In his final arguments to the jurors, Groenweghe called Johnson’s accusers “promiscuous.” Hands in his pockets, eyes downcast, he told the members of the jury that these young gay men “have a lifestyle I don't understand, that many of us don't understand.”

But, he said that HIV criminalization laws weren’t put on the books by legislators just to protect them, but to protect the public health — including the health of the jurors. Compared with the murder cases he’d tried in his career, Groenweghe said, this one was worse: A murder ended when a gun or knife killed someone, but the AIDS virus that passed through Johnson could still be killing people for years. From the perspective of HIV and its “mindless agenda,” he said, Michael Johnson was the “perfect host,” because he helped the virus spread by having sex “with one young man after another.” HIV could wind up killing someone who had “never heard of Tiger Mandingo and who might not even be gay” — like, he said, the wife of the man who didn’t press charges.

While the jury was sequestered to deliberate the sentence, spectators filled the courtroom for one of the only times during the trial. But not present was Mills, who had to return to Indianapolis to care for her children, or even Michael’s mother, who had hitched a ride back to her home in Indiana with Mills.

Kimber Mallett — a professor of the class in which Johnson was arrested almost two years before — was the sole person present who knew him and would see what would happen to him.

It took the jury about an hour to return with a sentence. As the gallery rose for them to file in for the last time, crying and sniffling were audible from several people in the warm room, including from the forewoman of the jury. When Judge Cunningham read that the jury was condemning Johnson to 30 years in prison for HIV transmission, there was an audible gasp in the chamber. There was absolute silence as he announced an additional 30.5 years of sentencing for three counts of exposure and one attempt to expose to HIV — meaning Johnson could serve 60.5 years in prison if the judge ordered the sentences to be served consecutively.

Cunningham scheduled a final sentencing hearing for July, when he’d decide if Johnson would spend three decades or six in prison, and the trial of Tiger Mandingo was adjourned.

In a post-trial interview in November, Groenweghe said that the jury’s verdict — not guilty on one count but guilty on the others — “showed that they were fair.”

He added, “I think it shows how seriously they took the public health problem.” To think of HIV as anything other than a terminal disease was “awfully foolish,” he said. It could be “managed,” he conceded, but “has no cure.”

Groenweghe also dismissed any suggestion of racial bias. His office had reviewed HIV prosecutions in St. Charles County and found that only two of the six defendants, or 33%, were African-Americans — clear evidence, he said, that there was no racial bias. But in Missouri, blacks make up less than 12% of the population — and in St. Charles, less than 5%.

The Jailhouse Interview

A few days after the trial, Johnson gave an exclusive hourlong interview to BuzzFeed News from behind a glass wall in the St. Charles County jail. Handcuffed, he had difficulty holding the black intercom phone to his ear.

Johnson said he’d expected nothing worse than a hung jury. But, he said, the jurors didn’t believe him when he testified that he had told his sexual partners he was infected because “the jury didn’t believe a person would ever be with a person” sexually “who was HIV-positive.”

Asked about the video that showed him denying he knew who Lemons was, Johnson said he was trying to remember who the person in the photo was and said that if the “prosecutor would have let the video go on,” it would have shown him eventually identify Lemons.

"This is something that could happen to other HIV-positive people. If I didn’t stand up, who would?”

An email obtained by BuzzFeed News shows Johnson’s lawyer was negotiating a plea deal of 10 years, which Johnson nixed. But he had “no regrets,” he said. “I could have been home sooner with my family, and they’d have loved me to come home,” Johnson said. But “I was never going to take a plea” because “it would have been morally wrong,” he said. “I wasn’t raised to give up because something is hard.”

Johnson said he was embarrassed that his family “heard things about my sex life” and about “me being promiscuous.”

“No one was meant to see” the sex tapes, he said, and he was mortified that Groenweghe made it seem as if he’d made them with 30 people. Johnson said he made the videos with repeat partners who, like Tryon, agreed to be taped.

Johnson said he was still being held in solitary confinement up to 23 hours a day, as he had been for several months. Yet he displayed a steadfast faith in the criminal justice system, along with a belief that he will ultimately be found innocent on appeal. “I couldn’t just let it be because I’m black, and I’m in a place where being gay and HIV-positive is hard, that you shouldn’t still believe that the system works.”

Asked about facing 30 years in prison, Johnson said, “I’ve thought a lot about how this is something that could happen to other HIV-positive people. If I didn’t stand up, who would?”

“I learned from this trial how wrong it is to criminalize people with HIV. Once you have it, you have it for the rest of your life. You will be looking over your shoulder forever, fearing someone could say, ‘This person didn’t tell me. Lock him up!’”

The Final Sentence

On July 13, Judge Cunningham ruled that Johnson could serve his sentences concurrently and sentenced him to 30 years in prison.

His attorney filed for appeal a few days later, and he has been moved to the Fulton Reception and Diagnostic Center, a Missouri state prison about a two-hour drive west of St. Louis. Lawyers said it’s not clear when Johnson might be eligible for parole. If he serves his full sentence, he would be set free when he is 52 years old — but when released he would still be a registered sex offender.

Johnson has no prior criminal record — something his public defender did not highlight for the jury. Still, his sentence is longer than the average sentence for almost every other crime in the state. According to the Missouri Department of Corrections, Johnson’s sentence exceeds the average for physical assault (19.9 years), forcible rape with a weapon (28.2 years), and even second-degree murder (25.2 years).

Johnson's sentence is longer than the average sentence for almost every other crime in the state.

After the trial, Filip Cukovic, one of Johnson’s sex partners, said that while HIV laws should stay on the books, “Getting 30 years for exposing someone to HIV is just silly.” He added, “It would be better for him if he’d killed someone instead.”

Recent prosecutions outside of Missouri involving HIV have resulted in far less severe punishments. In Washington in 2014, a Seattle man charged with transmitting HIV to eight men was was placed under court order and sent to counseling. In California this year, a San Diego man was given six months in jail for lying to his partner about having HIV and ordered to stay off of hookup apps such as Grindr. And in February, judges of the nation’s highest military court, the U.S. Military Court of Appeals, overturned the HIV conviction of an HIV-positive Air Force sergeant because “prosecutors failed to prove that any” of his sexual acts at a swingers’ party “were likely to transmit HIV to his partners.”

But in Missouri, two months after Johnson was sentenced, David Lee Mangum of Dexter was sentenced to 30 years for exposing others to HIV.

Missouri’s harsh sentences cut against a national trend in medicine, which is moving away from dealing with HIV as a criminal matter. A wide swath of medical authorities — including the American Medical Association, the Association of Nurses of AIDS Care, and even the medical director for corrections medicine for the Saint Louis County Department of Health — believe prosecuting people for not disclosing their HIV status could facilitate an increase in its transmission and harm the public health.

Even Charles Pfoutz, the accuser whose testimony did not lead to a conviction, said he didn’t think Johnson “deserved 30 years” and should have gotten “like in California, six months to a year.” In a phone interview in October, Pfoutz said he initially told the prosecuting attorney, “It's fifty-fifty. I’m responsible, he’s responsible” for his HIV transmission.

Which raises a question: Who gave Johnson HIV?

Johnson says he “can’t say who.”

“There’s always an idea, but I wouldn’t want to say if I don’t know for sure.”

If he did, would he want them prosecuted?

“No, I wouldn’t wish harm on anyone,” he said, shaking his head slowly behind the thick jail glass. “I wouldn’t want this to happen to anyone.”